This skill track is under construction!! —

📋 Content

- This skill track is under construction!!

- 📋 Content

- Objects

- Classes

- Methods

- Construction Work

- Fine Print

- Rules for

__str__: - Composition

Learning OOP can be tricky for three reasons:

- It is a very different concept from the imperative programming that usually is taught to beginners.

- A lot of problems and descriptions are given in natural language with all the ambiguity and implicit information that comes with it. This can make understanding the issues to be solved a lot more difficult.

- It introduces a lot of technical terms with very specific meaning and its own graphical notation (called UML).

Objects

A Little Story

Let’s imagine that we analyze blood data of patients for our research. To do so, we have a huge amount of samples from various patients that need to be tracked, catalogued and analyzed.

We will start out simple and track the ID numbers of each sample. A list will do the job fine.

sample_identifiers = ["0123", "0124", "0120a", "0120b"]

To give proper credit, we should also track who collected the samples. So… how about a second list?

sample_collectors = ["Max", "Yvonne", "Max", "Kristin"]

Introducing Objects

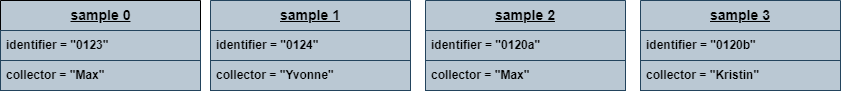

We obviously need a better way to model more complex data. For that purpose we introduce the idea of an object. An object represents an amount of data that belongs together in the context of a program. In our example each collected sample could be represented by an object:

Classes

A more generalized approach

Each of these samples has the same kind of information attached to it, so we can describe what a sample in general looks like: We can summarize these common features as: “Every sample has an identifier and a collector”.

This abstraction is called a class. The “variables” that each object of the same class has are called attributes. In our case these are identifier and collector.

An object that is of a certain class is called an instance of that class. Instantiation thus is the process of creating a new object from a class.

Let us see how to write this down in Python, step-by-step:

Note how the output of printing an object directly is pretty awkward. We will learn how to improve that later.

There is one further important insight: Classes are data types. Try:

my_sample = Sample()

type(my_sample)

This means that you can use any object as a value for variables or put them into a function as values for parameters.

Methods

A Method to the Madness

For now let us focus on how to extend our new class with a bit of functionality. To do so we will define something that reminds us of functions. In the context of OOP this is called a method. Usually, a method needs to refer to a particular object which it operates on. In Python this object is passed in as the first parameter, called self. This parameter will be filled in automatically by Python if you call the method via the .-operator, hence you do not need to to pass self into the method even though it is part of the list of parameters in the method signature. Let’s take a look at another example:

The output of print_me() is not very nice or helpful at all. If you want to pretty-print an object you will have to implement a special method called __str__(). More on that later…

Construction Work

It would be really nice if we could set the instance attributes directly when creating an instance, wouldn’t it? A special method, called a constructor, can help us with that:

Fine Print

Now we have the most essential components to build ourselves a first useful version of a Sample class.

Rules for __str__:

- The method signature is

__str__(self). - It must return a string.

- The method will be called by

print()to figure out how to display an object on the command line.

Composition

Putting Things Together

We now need to combine this new class with our Sample. In a picture, the current situation looks something like this: